Dante’s Hell and Its Afterlife

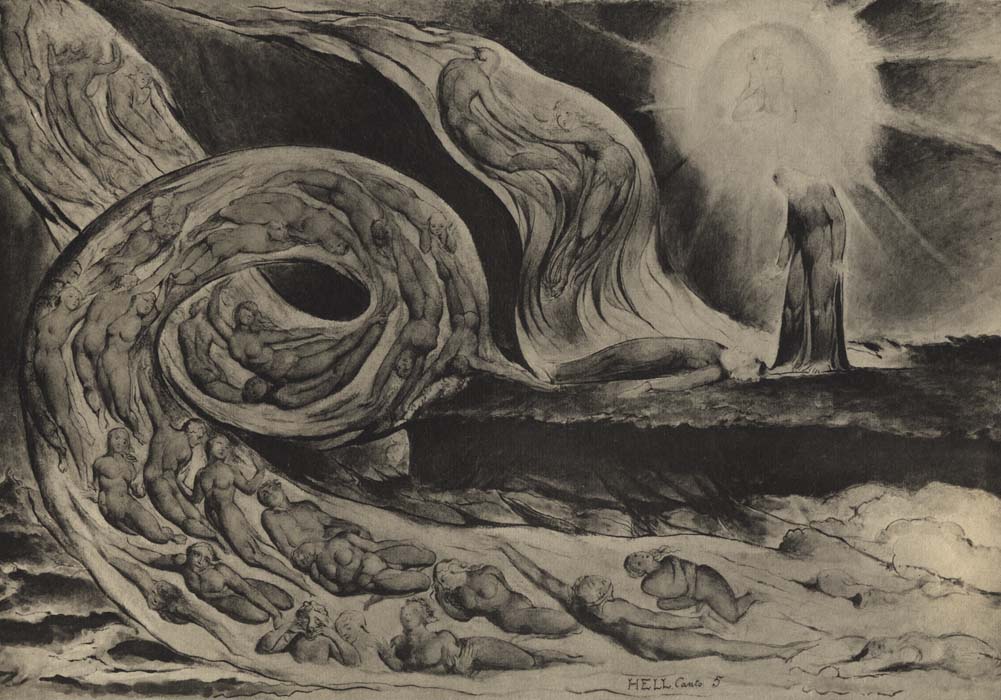

“Today’s features include updates on Francesca and Paolo’s love affair, a human hurricane, and today’s unlucky lottery numbers,” announces the anchor of Circle 2 News.

The infernal meteorologist, live on the scene, wonders why he must report each day on a storm that has been buffeting souls, once subject to the winds of passion, “for the past millennium with unchanged conditions.” After informing viewers that the Trojans, despite their vaunted defense, were done in by “the Greeks’ tricky plays,” the sportscaster reveals that Paris, newly arrived in the circle of lust for having abducted Helen, thought “the great Achilles was just overrated.”

These lively reports from beyond the grave don’t emanate from the bowels of Dante’s hell in 1300 but are broadcast from an elegant room in the “Tower” or Main Building on a bright spring morning in 2014. The reporters are not glib Florentine chroniclers but savvy UT students enrolled in “Dante’s Hell and Its Afterlife,” the large-format signature course I have the pleasure of teaching each year. (I thank San Juanita Millan, Aaron Cooper, and Moises Rodriguez for their excerpted dialogues.)

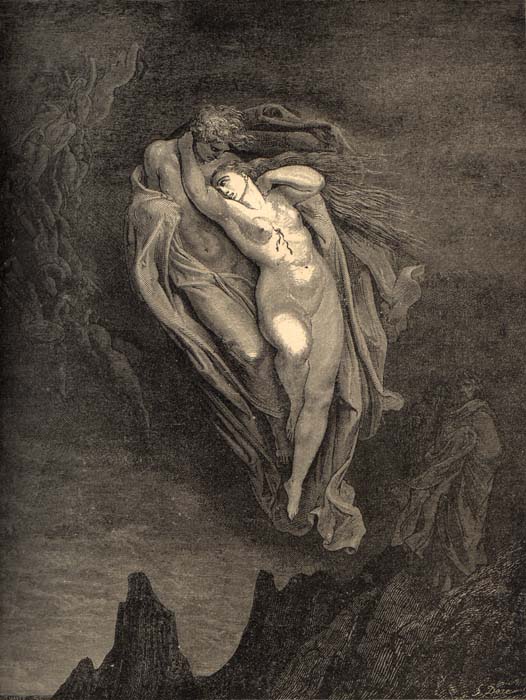

I don’t imagine the character Dante had nearly as much fun trekking through the Inferno’s nine circles of lost souls. But the poet Dante even and especially enjoyed creating this part of his Divine Comedy in the early fourteenth century. And many writers, artists, and filmmakers inspired by Dante have clearly delighted in adapting his vision of hell to their own time, place, and medium. Students likewise take pleasure in exploring the poem and its continuing relevance, especially when encouraged to add their own voices to this tradition by creatively bringing Dante’s old Italian poem into the present.

In this joyful spirit “News from Hell” and other course assignments embrace the classical idea that poetry and other serious creative work aims “to delight and instruct at once,” as the Roman writer Horace put it over two thousand years ago (The Art of Poetry, trans. David Ferry [New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001], 175). Exemplified by Dante’s Inferno, this reciprocity of pleasure and learning—the way they mutually enhance and reinforce one another—guides our study of the poem and its cultural legacy.

The learning and instruction half of this equation means more than mastering the content and significance of the Inferno and other course works; it also means using that knowledge to acquire and refine tools necessary to excel within and across majors, disciplines, and career paths. “News from Hell” helps achieve this objective through a series of integrated activities developing and assessing multiple skills. Students learn the importance of effective collaboration by working in teams of newscasters and reporters (3-5 students per team) to create a mock TV program covering a specific circle of hell. Each group decides the format of the newscast and the individual roles that best suit its conception. Most arrangements include a news anchor with colleagues in the studio or journalists reporting live from the scene, often by interviewing a memorable creature or character.

Team members must be able to understand, summarize, and select pertinent details from Dante’s text to craft coherent content for their individual segments. They must also do background research on their contribution to the news program. Envisioning this task as a stage toward conducting more sophisticated research later in the semester, I work with TAs and the course librarian to teach students how to find, incorporate, and document basic information from reliable sources, such as the Gale Reference Library and peer-reviewed reference works. A worksheet includes questions to help students identify topics, ascertain the type of information required (mythological, philosophical, historical, theological), and evaluate the credibility of sources.

The collaborative format of “News from Hell” creates a supportive environment in which students—shy ones in particular—gain skill and confidence in presenting their work orally to classmates and instructors. Many teams create their own “user groups” in Canvas (the course learning management system) so they can easily share information and make progress on the newscast outside of class. The TAs and I use two lecture periods to listen and provide hands-on feedback to each news team before the final performances, which are assessed for presentation style, organization, subject knowledge, language control, and elocution. (These workshops have the added benefit of enabling me to meet individually with every student in this large class early in the semester, an encounter—however brief—that opens the door for virtual and face-to-face conversations outside of class time.)

Students then write up their individual work in the form of an article or opinion piece for a newspaper or magazine. Here, too, students receive substantive feedback on their work, in this case through on-line comments and a detailed rubric examining analysis of Dante’s text and integration of research in addition to organization and writing mechanics. While teaching students to articulate a deeper understanding of Dante’s complex poem, this multi-faceted project develops and sharpens their research, writing, and oral presentation skills.

An outcome of the Information Literacy Enhancement Program for signature course instructors, “News from Hell” is a building block of the major research assignment in the second half of the course. To produce an essay showing how another creative mind adapts, endorses, challenges, or refutes something Dante says or does in his Inferno, students are taught in carefully sequenced stages how to gather and evaluate research sources, assemble an annotated bibliography, write an outline and tentative thesis, and revise and edit their work.

The extraordinary assortment of works they put into dialogue with Dante’s medieval poem furthers my own education in contemporary culture. Novels by Dan Brown, Karen Russell, Brett Easton Ellis, and Jodi Picoult; films like Clerks, Se7en, What Dreams May Come, and Pirates of the Caribbean; music by Lady Gaga, Alesana, Kanye West, and Roky Erickson; television shows like Lost, Futurama, Supernatural, and Gossip Girl; and of course a healthy (?) serving of videogames—student projects on these and other works affirm the pervasive resonance of Dante’s Inferno in their own lives.

I’m always delighted to learn that the academic majors and interests of my students are as varied as the works they study in relation to Dante. Roughly half the students in a typical class lean toward the humanities and social sciences and half toward business and the sciences. They, in turn, are happily surprised to learn that the Dante scholar before them holds an undergraduate degree in mathematics and computer science. After I explain that at their age I enjoyed my humanities and science courses equally well, we have a productive conversation about majors, disciplines, and education in general.

I tell them the

training I received as an undergraduate science major helped me to write

stronger papers on literature, philosophy, and history. The depth of analysis

and argumentation essential to effective writing likewise helped me to solve

mathematical problems and write computer programs. I honestly can’t say that

the influence flowed more in one direction or the other. But I do know from my

“bipartisan” academic background the importance of learning to think

logically and write well, two of the core objectives of all signature courses.

Nor does the value of these skills diminish after graduation. Nearly all 318

employers participating in a 2013 survey conducted on behalf of the Association

of American Colleges and Universities include among their highest priorities

the ability of college graduates to innovate, think critically, communicate

clearly, and solve complex problems—regardless of their majors.

“Dante’s Hell and Its Afterlife” is the course that best exemplifies my teaching philosophy. I aim to meet students where they are and motivate them with creative assignments like “News from Hell” and innovative tools—including UT’s Danteworlds website—to reach high standards of academic achievement. “Don’t be frightened, I know how to handle this,” Virgil reassures his companion when they’re threatened by a squadron of fierce demons, one of many trials facing Dante on the road through hell to spiritual and intellectual enlightenment. The signature course also promises meaningful rewards for meeting the challenges of an educational journey. But unlike poor Dante, we have a hell of a lot of fun along the way.

[First published in Signature Course Stories: Transforming Undergraduate Learning, ed. Lori Holleran Steiker (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2015), pp. 43-45]